Although you are a newbie or a big fan of Japanese manga and anime, you must be similar to the type of character well-known as an anime catgirl. They are so cute and appealing that they are beloved by a variety of people not only in Japan but also around the world. Many Japanese anime goods, taking the inspiration from these cat girl characters, have been created and become one of the exclusive Japanese items that can be only found in this beautiful country.

So, what do you know about anime cat girls? Today, Janbox will show you some interesting information about their origin, history, characteristics, and the TOP 25 best adorable anime cat girls of all time. Let’s go!

1. What Is An Anime Cat Girl Called? History Of Cat Girls

An anime cat girl (猫娘: Nekomuseme; or 猫耳: Nekomimi) is basically defined as a human girl with feline traits like cat ears, slitted pupils, a cat’s tail, a cat-like mouth, and other feline characteristics. Catgirls are found in many fiction genres and especially in Japanese anime and manga. A catgirl will show many feline qualities, for example folding her hands in the shape of paws, licking or nuzzling her paws, making literal cat noises, or acting extremely adorably. These characteristics make anime cat girls cute and childlike.

So, what are catgirls’ origins and history? Are you curious about it? Go back to the past! As can be known, early manga and anime were strongly inspired by early American cartoons, beginning during the 1930s-50s. Japanese anime and manga artists got inspiration from Disney’s animal-people that were known as funny animals or anthro cartoon characters. Take Mickey Mouse, Oswald the Lucky Rabbit, and Donald Duck as typical examples, these cartoon characters are some of the biggest inspirations for anime and manga authors in Japan.

What’s more, the Japanese have always been fond of cats, which made a great influence on the birth of anime catgirls. With the love of cats and the aspiration to create an original cartoon character that is the same as the most famous American ones, Japanese people made cat-like characters in many early manga and anime.

According to Wikipedia, the first modern example of a cat-eared woman appeared in Kenji Miyazawa’s 1942 work, named The 4th of Narcissus Month. Until 1949, Mitsuyo Seo produced the first anime with the title ‘The King’s Tail (Osama no Shippo)’ which involved anime catgirls. Since then, a catgirl or sometimes a cat boy has become an important character in lots of well-known anime. There are some anime including only characters with cat ears such as Tokyo Mew Mew and Loveless.

2. Why Do People Find Cat Girls Fascinating?

There is a viewpoint that the cute anime catgirl in Japanese culture is similar to the Playboy bunny in the West, with both employing animals linked to feminine qualities to accentuate the sexual appeal of either fictional characters or women dressed in similar attire.

However, catgirls are usually depicted as innocent, carefree, and naive, with an emphasis on cuteness over sexiness. This reflects the concept of moé, which is central to many young female anime characters. Their appeal is heightened by adding cat-like traits such as ears, collars, tails, and playful behavior. This aesthetic focuses on innocence and charm, making it distinctly less sexualized compared to the Playboy Bunny.

Catboys and catgirls can embody various character traits, such as tsundere or dere-dere, but they most commonly fill roles like “manic pixie dream girl” or “magical girlfriend”. These characters are typically energetic, playful, and feminine. In anime, cat ears and tails are often used to express a character’s emotions, providing a visual shorthand that helps convey the emotional state of the character.

>> See more: What Is The Difference Between Manga And Anime?

3. Top 25 Best Cute Anime Cat Girls Of All Time

Uncover the world of anime catgirl characters by checking out the top 25 that have left an unforgettable impression on fans. This list will help you find the best catgirl anime characters that resonate with your preferences. Now, let’s explore the most popular anime catgirl names, their appearances, and the traits that define them.

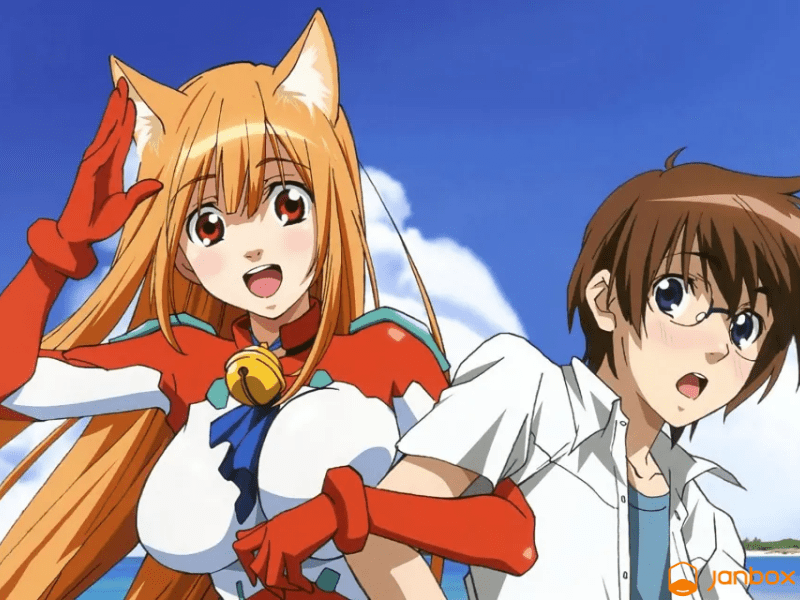

3.1. Eris (Cat Planet Cuties)

If you are a fan of anime catgirls, you must know about Eris from Cat Planet Cuties, a young scout for the Catain people. As an ambassador of the Catain people, Eris was sent to Earth to explore this planet. She is beautiful, tall, and well endowed, which attracts attention from both people and cats as well. During her time on Earth, she makes friends with inhabitants and lots of other actual cats here.

What’s about her love? Eris falls in love with her high schoolmate named Kio while she explores Earth. She is described as an expert fighter when she is in combat.

3.2. Melwin (Cat Planet Cuties)

When it comes to Cat Planet Cuties, Melwin is also one of the anime cat girls beloved by lots of manga and anime fans. She is the First Officer of the Catain Starship. In comparison with the other catgirls, she is thinner and smaller-chested and has short blue hair.

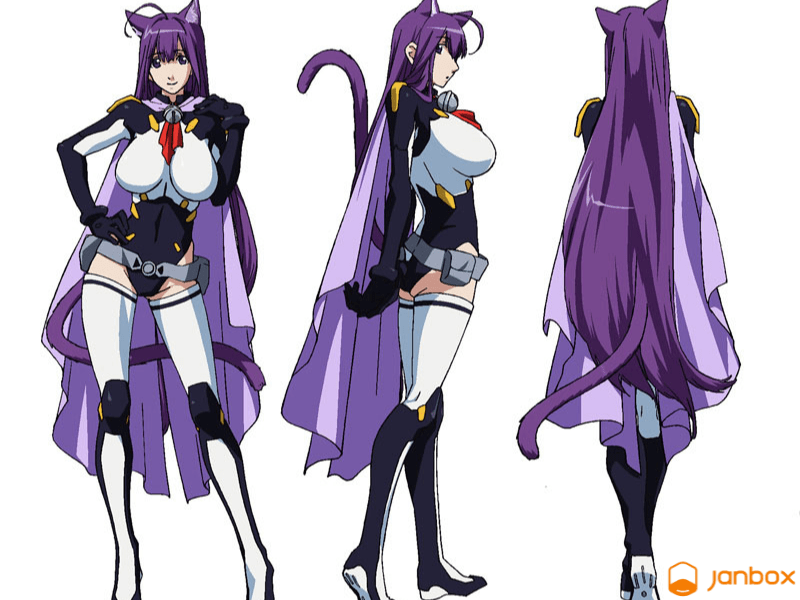

3.3. Kuune (Cat Planet Cuties)

Kuune is the Starship captain of the Catian girls and the head negotiator for establishing diplomatic relationships with the leaders on Earth. She loves Okinowian food as much as Eris does, with an almost similar reaction. Kuune has the largest chest size and incredible height, compared with all the other Catians. We must be impressed with this character, especially when she enters into a negotiation. It is the fact that Kuune is an ice-cold negotiating partner who hardly agrees with disadvantageous compromises.

3.4. Chaika (Cat Planet Cuties)

Chaika is seemingly the youngest of the group among the Catian Starship Crew. Although she is assigned as the leader of the ship’s analysis team, Chaika is in charge of guarding the Catian Embassy whenever Eris and others go out. She is said to be more open-minded than the Catians because she does not feel embarrassed about exhibitionism and expression of sexuality as well.

3.5. Yoriko Sagisawa (Da Capo)

Misaki/Yoriko Sagisawa, from Da Capo, is a young girl who stays at home and observes the world through her room window. She has a cat named Yoriko. In the game, Misaki, after having her wish granted by the sakura tree, owns the body of her cat, which transforms into a catgirl version of herself. This is quite different from the anime.

In the anime, Yoriko is transformed into a maid resembling Misaki but with brown cat ears and jumps out of her owner’s window to explore the world outside in her place. Yoriko has a fear of people after an incident with a few children. However, she slowly overcomes that fear thanks to the help of Junichi. Sadly, she is not able to stay in her human form for long because of the giant sakura tree being cut down.

During her last day as a human, Yoriko asked Junichi to have a date with her at his school. After playing around the school, she tells him her secret and disappears. Finally, Yoriko goes back into the house in cat form.

>>> Read more: Why Are Anime Characters So Attractive? Janbox Japan

3.6. Ao Nanami (Yozakura Quartet)

Ao Nanami from Yozakura Quartet is a thin and cute anime cat girl. She has short blue and chin-length hair, along with two antennas looking like cat ears over her head. Moreover, she also possesses light skin and blue eyes. Ao Nanami usually puts on a black hat toque that helps to form her cat’s ears. Sometimes, she also wears a black Alice band to hide her ears in case she does not want to stand out as a youkai.

This anime cat girl is often seen in summer clothes like a dark sleeveless mini dress with blue buttons and a white-collar as well. Dark-colored boots are her favorite. It is undoubted that Ao Nanami is one of the best Anime catgirls.

3.7. Cyan (Show by Rock)

In Shoe by Rock, Cyan is a catgirl who is sucked into the Sound World. In addition to black ears and a tail, she also has shiny turquoise eyes and dark blue hair formed in numerous short ringlet curls. Cyan wears a white frilled cloth that is similar to a maid’s hat. Her black blouse looks so impressive with white frilly material at the chest combined with a row of black buttons.

She is a skillful guitarist whose instrument, Strawberry Heart, becomes a magical guitar that can talk. They must work together not only to vanquish the dark monsters to save the Sound World but also to help her escape.

3.8. Felicia (Darkstalkers)

Known as an enthusiastic and optimistic anime cat girl, Felicia from Darkstalkers is really into singing, dancing as well as making friends with people. She desires to live peacefully with human beings and doesn’t resort to fighting unless she is unable to avoid it. That is the reason why Felicia is different from all the other Darkstalkers.

3.9. Himari Noihara (Omamori Himari)

Omamori Himari is a manga and anime series about an orphaned boy, Yuto Amakawa, meeting Himari Noihara, a samurai spirit cat girl. She takes an oath to protect Yuto Amakawa from dangers including fighting against monsters that want to kill him. The anime cat girl Himari shows up in an extremely appealing appearance, which is engraved on viewers’ memories.

She has long black hair with a blue tint, some bangs, and violet eyes. Himari usually ties her hair in a long ponytail with a pink bow, which makes this anime cat girl cute and attractive. As a master swordsman, she can combat and defeat dark energy easily.

3.10. Nozomi Kiriya (Mayoi Neko Overrun!)

One of the best anime cat girls we must mention is Nozomi Kiriya from Mayoi Neko Overrun. Well-known as a light novel series with a manga and anime adaption, Mayoi Neko Overrun is the story around Takumi Tsuzuki and his friends because they often visit the Stray Cats cafe. Then, his sister, Otome Tsuzuki, brings home a beautiful but mysterious girl named Nozomi Kiriya to live with them.

After being taken by Otome Tsuzuki, Nozomi lives in the Stray Cat cafe. She is quite mysterious and does not unveil much about herself except for her name. Nozomi frequently reveals many characteristics of a catgirl including saying “Nya~” (meaning “Meow”), being innocent, and having a typical hairstyle that looks like cat ears. However, she is skilled at piano, sports, and studies.

>>> Read more: Top 10+ Best Anime Online Stores To Buy Anime and Manga

3.11. Ichigo Momomiya (Tokyo Mew Mew)

In Tokyo Mew Mew, Ichigo Momoiya is the main character as well as the leader of the Mew Mews. When transforming, she becomes a catgirl with cat ears, a tail, and a collar. Along with these physical traits, she is also able to turn into a real cat form. It is explained in the anime that Ichigo Momoiya’s DNA was merged with an Iriomote cat, which makes her an actual cat in reality.

3.12. Koneko Toujou (High School DxD)

When it comes to anime cat girls, we can’t miss Koneko Toujou from the anime and manga series “High School DxD”. Koneko is a girl with gold eyes and white hair. She often wears black cat-shaped hair clips on her hair, one of which has the data on artificially producing new Super Devils. When transforming into Nekomata state, she becomes a cat girl with cat ears, tails, and cat-like pupils. In the progress of the series, Koneko starts to display more feline traits, which makes her become a famous member of the catgirl club.

3.13. Blair (Soul Eater)

Blair from Soul Eater is a catgirl who can transform between an actual cat and a human form. When in her regular human state, she possesses cat ears, a tail, and fangs in her mouth resembling a cat’s. In her full cat form, she takes after a purple cat with yellow eyes, a smaller witch’s hat, and a collar. In the anime series, Blair is known as a cat witch, but she used to be mistaken for a normal human witch by Maka as well as Soul Eater themselves for a short time.

3.14. Kyaru (Princess Connect! Re: Dive)

If you have ever seen Princess Connect! Re: Dive, you will never forget the anime cat girl Kyaru. The evil Kaiser Insight sends Kyaru on a mission of supervising Yuuki and finally assassinating Pecorine. However, when she nearly gets to her targets, she hesitates and feels confused about whether she should complete her mission or not. When she transforms into a catgirl, she has cat ears, tail, and ability to climb excellently.

3.15. Chocola (Nekopara)

In Nekopara, Chocola is well-known as a straightforward and playful cat girl, different from her twin sister Vanilla. She not only has cat ears and tail but also wears a bell around her neck. Because of her happy and childish personality, Chocola tends to jump into action without thinking everything through. It is the same quality as an actual cat. However, she is so friendly and beloved by all people around her. Chocola works with her sister at La Soleil and has a close relationship with the protagonist, Kashou Minazuki.

>>> Read more: Top 18 Best Websites To Buy Anime Figures From Japan

3.16. Vanilla (Nekopara)

As mentioned above, Vanilla and Chocola are twins. Vanilla appears with the opposite personality of her sister. We will find her as a quiet girl who hardly expresses emotions. Although Vanilla is the youngest of the Minaduki catgirls, she is very smart and good-hearted. She is fond of her sister and likes going out with Chocola almost every time.

3.17. Coconut (Nekopara)

Another anime cat girl in Nekopara we must mention is Coconut. Needless to say, she is a calm and appealing girl. Coconut is always loyal to her master. Owing to being beautiful and having physical power, she is not good at coordination skills. However, it doesn’t matter because she always tries to improve herself and does not let this weakness prevent her from helping others. Coconut loves to be seen as a cute girl, but she gradually learns how to promote her strength.

3.18. Shizuka Nekonome (Rosario + Vampire)

Shizuka Nekonome is a cute anime cat girl and the homeroom teacher of Tsukune and Moka. Furthermore, she is also the advisor for the Newspaper Club. Shizuka is a little happy-go-lucky in her attitude and sometimes unaware of certain things. As said in the anime, her favorite food in the human world is raw fish. She is very kind and girly.

Shizuka seems to know that Tsukune is a human being, but she does not bother about it because she believes humans and monsters can get along together. Due to being nice, she easily loses her temper and feels embarrassed when someone reminds her of tail showing.

3.19. Alicia Rue (Sword Art Online)

Alicia Rue is another name in the list of best anime catgirls. Alicia Rue is a supporting character in the Fairy Dance Arc, and then a reappearing character in the Sword Art Online series. One of the things making her different from other catgirls is that her cat ears are on the sides of her head, instead of on top. What’s more, she wears a bell collar and uses clawed weapons to stand out her feline characteristics. Besides, Alicia Rue has a petite figure with wavy and blonde hair. She usually wears a one-piece armor that shows her tanned skin.

3.20. Ibaraki Douji (Onigiri)

Ibaraki Douji is one of the characters in Onigiri. She is a happy, adorable, and curious girl. Ibaraki is fond of doing foolish things with her friends. Especially, she loves drinking alcohol. In the game, Ibaraki is a half-Oni that is the same as the player’s character. Her job is to run a traveling bar.

>>> Read more: The 17 Types of Japanese Traditional Dolls You Need To Know

3.21. Rem Galleu (How NOT to Summon a Demon Lord)

Rem Galleu is an anime catgirl and also one of the main characters of the series. She is a short Pantherian girl with long black hair falling to her waist. Besides, a special thing about her appearance is that both her ears and tail are beautifully black, which is rare to see in other Pantherians. She possesses expressionless almond-shaped green eyes, along with spruce eyebrows, making others feel the strength of her will. Rem Galleu can move at a super-fast speed and has a strong offensive ability.

3.22. Yoruichi Shihōin (Bleach)

Yoruichi is a supporting female character in the Bleach franchise. She has brown skin, golden-colored eyes, and long purple hair in a ponytail. Her standard outfit includes a black sleeveless and backless undershirt, an orange over-shirt, a big beige band around her waist, two white straps on her shoulders, black stretch pants, and a pair of brown shoes. Yoruichi can transform into a small black cat for a long time. In a cat form, she has a typical male voice along with golden eyes. She is a smart and witty anime cat girl.

3.23. Rin Shaomei (Shining Tears x Wind)

Have you ever seen Shining Tears x Wind, an animated TV series which is based on the games, Shining Tears and Shining Wind? And Rin Shaomei (also known as Lin Lin) is a recurring character in the Shining series. When in her catgirl form, she is described as a more serious and calmer character. Rin Shaomei is an antique seller of the Beast race in the game.

3.24. Sasahara Natsuki (Hyper Police)

Sasahara Natsuki from Hyper Police is a sweet and kind cat girl. She is always friendly and eager to protect the weak, and uphold the law. She shows feline personalities like eating cat food, playing with string and other moving objects, or grooming herself as a cat. Thanks to her capacity of creating electrical shocks, she is invited to take part in the Police Company by Batanen.

3.25. Dejiko (Di Gi Charat)

The last anime cat girl we would like to introduce to you is Dejiko from Di Gi Charat. She is a catgirl completely in her characteristics and appearance as well. Along with her cat ears and tail, she often wears three bells; including two in her hair and one around her neck. What’s more, she looks so cute in her cat that resembles a cat’s face. Although Dejiko possesses an adorable appearance, she is also powerful.

>>> Read more: Best Japanese Proxy Service: What to Know and Who to Use?

4. Buying Anime Catgirl Merch And Gifts With Janbox

If you’re an avid fan of catgirl anime characters, Janbox is the ideal place to find all the catgirl merchandise you’re looking for. With a broad selection of products featuring popular feline-inspired characters, Janbox has something for every collector. Let’s delve into the world of anime catgirl goods and discover how Janbox can help you grow your collection. Here’s the instruction on how to purchase goods inspired by these cute characters on Janbox:

Step 1 – Create an account on Janbox Website or App

Visit the official Janbox website or download their app to get started. Janbox gives international customers access to authentic anime catgirl merchandise and gifts. To make the shopping experience smoother, it’s a good idea to register an account before you begin your purchase.

Step 2 – Make an order for your favorite anime catgirl product

Use the search bar to type “anime catgirl” or the name of a character you love. Janbox offers a selection of authentic anime catgirl merchandise sourced directly from Japan. Whether you’re looking for official items, unique collectibles, or limited edition products, you can be sure you’re getting authentic, high-quality goods that aren’t commonly available.

After finding the merchandise that catches your eye, click on it to see more details about its size, features, and price. Confirm that you’ve selected the right option before adding it to your cart.

Step 3 – Complete the 1st payment

Once you’ve double-checked your cart, proceed to payment, which will include both the product cost and any applicable fees. Janbox supports various payment methods which are accepted globally, such as credit cards and PayPal, providing a secure and straightforward checkout process for your anime catgirl products.

Step 4 – Review shipping details and wait for your order to arrive home

Janbox facilitates global shipping from Japan to your doorstep. Make sure to check the shipping information to confirm that the product can be shipped to your address. After completing the payment for shipping and any extra services (e.g: consolidation), Janbox will take care of the rest. Then, sit back and wait for your authentic anime catgirl merchandise to arrive directly from Japan.

Conclusion

In short, Japanese cat girl characters are beloved by lots of people, especially manga and anime fans. Some of them are cute, little, and more vulnerable but some are brave, dominatrix, and strong. No matter what characteristics they are, they always attract others’ attention thanks to their fantastic appearance. So, which anime cat girl is your favorite character? Let us know by leaving your comments. Janbox hopes that this article about the best anime cat girls is interesting and informative to you.

Website: https://janbox.com

Email: [email protected]